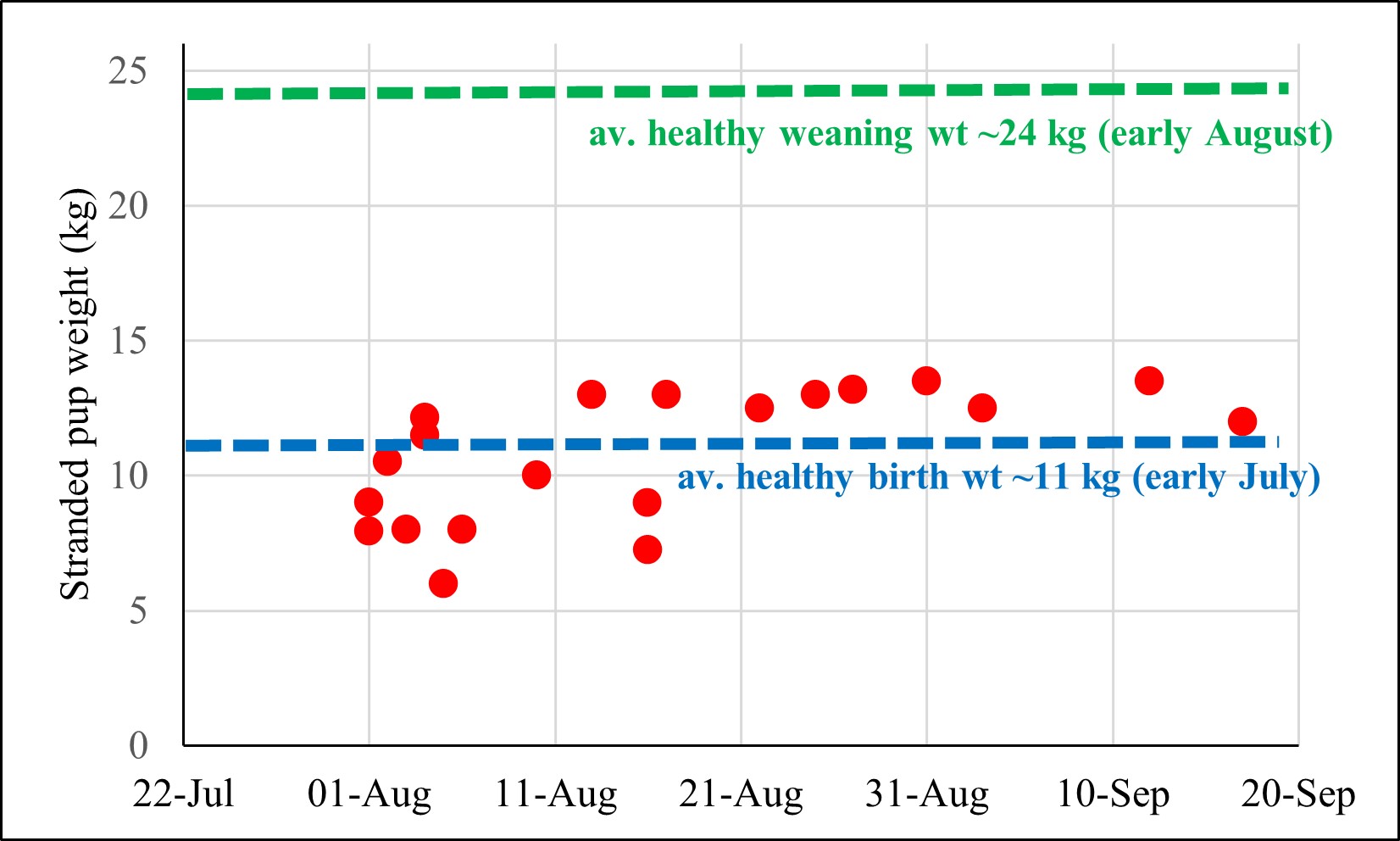

For the past few years dying harbour (or common) seal pups have been stranding along the Tees Bay coastline, north as far as Northumberland and south to north Yorkshire. This has been happening in late summer - from the end of July to September, with a peak around mid-August - when the pups are newly weaned from their mothers.

![]()

This little pup, born in the Tees seal colony in late June 2024 and cared for by its mother, had little chance of reaching two months of age.

In late June-early July 2024 there were ~23 pups born at Seal Sands and cared for by their mothers.

Seal pups following their mothers at Seal Sands (June-July 2024)

Body weights of pups stranding in north-east England in the summers of 2021, 2022 and 2024

This past summer (2025), it has been the same sad story. We counted 21 pups, many still with their mothers, at Seal Sands in mid-July. By the end of August at least 19 pups had stranded along the Tees bay coastline - and at least two more further north. We received word from local vets in time to obtain samples of the mouth rot area (for bacterial culture) and fatty tissue underneath the skin (for PCB analysis) from eight of these pups.

Left: Healthy weaned pups (Co. Down, N. Ireland), more than 20 kg. Right: stranded emaciated Tees pup, weighing only 7 kg

As well as being underweight, most of these pups also had "mouth rot" - where the soft tissue in and around the mouth, and especially on the hard palate behind the front teeth, had rotted away due to the action of bacteria. We have now had the results of bacterial culture from the infected mouth area of 13 pups - five in 2024 and eight in 2025. In every case the lab has reported profuse growth of anaerobic bacteria, i.e. those that live without oxygen. However, the predominant bacteria that were identified, most of which are potentially pathogenic, were different in each pup in 2024, leading us - after conversations with microbial specialists - to suspect the mouth rot was the work of any kind of opportunistic bugs that had multiplied out of control and upset the normal balance of the oral bacterial flora. In 2025 the pups all had mixed bacterial growth, including E.coli, suggestive of a recent local sewage spill.

Because the pups were mostly stranding after leaving their mothers (at about 3-4 weeks old) and starting to disperse out of the estuary, we initially thought the pups might be being infected by the bacteria in the coastal waters, on the sea bed or in the small fish that they were eating, although it seemed unlikely that every Tees-born pup would encounter such an infection in the immediate aftermath of weaning. However, the one thing that every pup does is to suckle from its mother for its first 3-4 weeks - and the Tees mothers are suckling their pups while they have been lying on the mudflats of Seal Sands and Greatham Creek, surrounded by industrial and sewage outfalls. When the pup suckles, its lips come into contact with the mud on its mother's belly, and when it takes the muddy nipple into its mouth, the mud will be pressed up against the roof of the mouth behind the teeth - which is the primary location of the mouthrot. If the mud is infected, it is possible this is how the mouth rot infection is initiated.

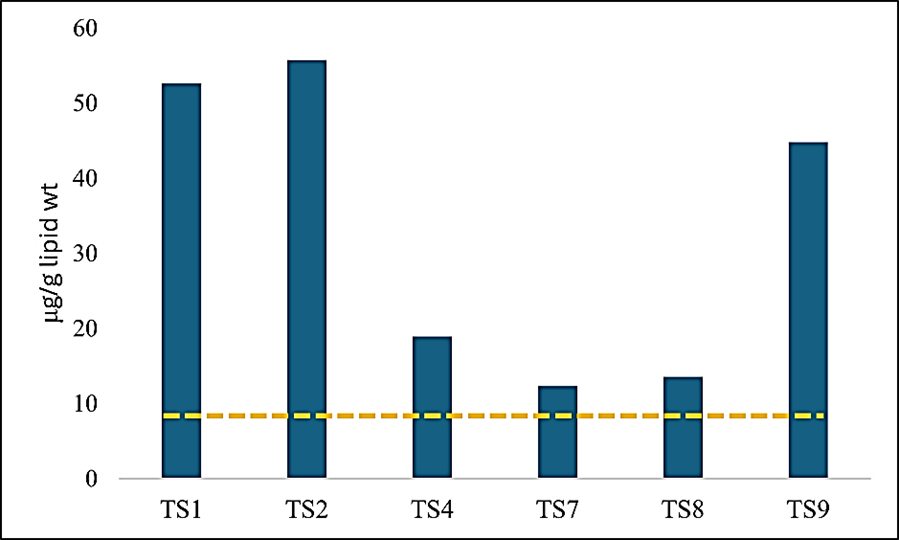

However, mindful of the human experience of ANUG and NOMA occurring in immunocompromised individuals, we have also been exploring this possibility in our seal pups - which are all so small and emaciated. This echoed the case of the Tees pups that died in the days after birth in 1989-93, and had high PCB levels in their fat layer under the skin. PCBs are known to cause both retardation of infant mammal growth and immuno suppression. The pups get their PCBs mainly from their mothers' milk as they suckle, and thereby fail to grow properly, even while their mothers are feeding them. Their mothers, presumably, acquire the PCBs from contaminated fish eaten during pregnancy and then passed to the pup in the fat-rich milk. PCBs were manufactured in the Tees until the production was banned in the 1980s; recent studies of PCBs in the sediments indicate they are still present.

Stranded pups from the Tees Bay area, underweight and with mouth rot - Left: pup has mouth rot on the lower lip, Right: mouth rot has extended to the pup's face. Both pups were so severely affected they had to be euthanised by a vet.

The six pups we analysed for PCBs in 2024 had levels above that which pups tend to be born underweight, fail to grow and thrive, and have poor immunity to infections – such as the mouth rot bacteria.

PCB levels in the fat of six pups analysed by TESS in 2024 - the yellow dotted line indicates the approximate level above which growth and immune suppression are thought to occur.

This is what we think may be happening to the Tees pups, although we need more post-mortem tissue analyses before we can be sure. In August 2025 we obtained tissue from the blubber layer of eight more pups from Tees Bay, and these will be analysed as soon as the funds are available.

To summarise, our current ideas of the causes of the Tees common seal pup morbidity are that the pups have failed to grow normally during the suckling period with their mothers owing to high levels of PCB contamination, which has also resulted in all the pups having a weakened immune system. While suckling, the pups mouths are likely infected by contaminated mud - possibly originating in part from sewage outfalls - on the mothers' nipples; the infection takes hold gradually as the pups' immune defences become progressively weaker as they suckle. When the pups leave their mothers, they naturally start to disperse out of the estuary; they may be unable to learn to forage on small fish owing to their infected and painful mouths, and become progressively weaker until they drift in the current and strand along the shore.

If our hypothesis of PCB contamination of fish in Tees Bay and sewage pollution of the Tees seal "headquarters" at Seal Sands turns out to be correct, what can be done to help the Tees common seal colony in the future? This could be used as a scientific basis for reviewing policy decisions on offshore activities in the Tees. We are also seeking information on sewage outfalls in the estuary, with the expectation control of these will soon improve. Our 14 samples to date represent almost a third of all Tees pups 2024-25 and the same analyses likely to not need to be repeated immediately. The research next year (2026) could instead focus on environmental eDNA of the surface mud of Seal Sands, which should identify the microbe species present in the mud. DNA analyses of the stranded pups' mouthrot may be compared with the mud eDNA to see if that strengthens our hypothesis.

We expect this heart-breaking common seal pup mortality to recur in 2026. Reference to the WHO report on "NOMA" suggests the mouthrot infection in our stranded seal pups may be equivalent to a stage 2 or early stage 3 NOMA infection, and at least a few of these pups currently being euthanised may still be treatable according to the medical treatment recommended for NOMA at these states. We hope we will be able to have a community-run seal pup hospital in the Hartlepool area to attempt treatment, feeding, and at least partial recovery of a few of these pups. However, even with vets and our volunteer team donating their expertise and time, funding will be urgently needed for veterinary and milk formula costs, and temporary premises - a yard with drain and running water, and accommodation for the volunteer team.

Our present Just-Giving page is: https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/tees-seal-pups

Our thanks to Sea Changers for funding seven of the post-mortem bacteriology analyses in 2025